The disease famously known as the “love disease” may carry romantic connotations, yet its actual consequences transform individuals into outcasts, not to mention its detrimental effects on the nervous system.

At the heart of the narrative lies one of the most renowned hypotheses surrounding the arrival of syphilis in Europe. While traditionally linked to Columbus’ return from Haiti in 1493, recent findings by scientists in Zurich unearthed traces of Treponema pallidum in ancient remains from Finland, Estonia, and the Netherlands. Despite these discoveries, the hypothesis remains unproven due to limited research on the subject.

The tale unfolds in the wake of Columbus and his crew’s triumphant voyage to the Caribbean in 1493, bearing gifts like tobacco, newfound lands for the crown, and the unexpected addition of syphilis. Undeterred by discomfort in their groins, sailors and soldiers eagerly sought solace in brothels after enduring long sea journeys. Squandering their earnings, they often reverted to mercenary work post the revelry, especially opportune amidst the brewing conflicts in Europe.

Sharpening his resolve to impress his 15-year-old bride Maria of Anjou, King Charles VIII set out to conquer Naples, capitalizing on territorial claims in Italy. Accompanied by an entourage of soldiers and, intriguingly, a cohort of regimental sex workers, the king sought to establish dominance and expand his realm. Charles’ infectious charisma extended not only to his maids but also to his troops, fostering an environment ripe for the spread of the “love disease.”

Claiming victory in Naples, Charles proclaimed himself the king of Naples and Jerusalem, alongside declaring himself emperor of the East at a youthful 24. Amidst a mélange of conquests and a burgeoning harem, the king orchestrated a grandiose two-month festivity culminating in an epic orgy. The revelry, flooded with courtesans from across Italy, inadvertently sowed the seeds of an epidemic within the army, wherein nearly a third of the soldiers fell victim to syphilis.

The grotesque symptoms of syphilis left an indelible mark, overshadowing even the horrors of the plague. Confusion shrouded the mode of transmission, fuelling myriad speculations and rumors. The Church, quick to attribute divine retribution to moral transgressions, stoked fear among the populace, who found themselves ensnared in both physical discomfort and spiritual turmoil.

Amidst the chaos and the rampant spread of syphilis, peculiar theories emerged regarding its origins. From whispers of cannibalism among Charles’ troops to bizarre notions of intermingling with horses leading to the affliction, the concoction of outlandish tales aimed at instilling fear and caution among the masses. The sinister outbreak coerced individuals to retreat into seclusion, wary of the unseen menace lurking outside.

The Italians and Spaniards joined forces to push back the impacted individuals afflicted with syphilis back to France. King Charles, not only faced disgrace but also encountered smallpox, leading to a transformation from a figure of humor to one of dread. Interestingly, despite leading an army of future Voldemorts, Charles managed to evade syphilis upon returning home. He embraced family life, fathered children who remained unaffected by venereal diseases, averting the common consequences associated with syphilis like premature birth or nervous system damage.

Disheartened by the turn of events, Charles disbanded his troops and sent the mercenaries back to their respective European towns, inadvertently spreading the “love plague” far and wide. The epidemic gained alarming momentum, reaching North Africa and Eurasia within 15 years. By 1512, syphilis had even made its way to Japan, prompting the nation to isolate itself from the world until the 19th century. Charles VIII’s demise, shortly after his return from Italy, was shrouded in suspicion, as he tragically succumbed to a head injury after an unfortunate encounter with a low doorway. His death marked the end of an era, leaving courtiers dissatisfied with the lasting moniker of the “French disease” due to the outbreak during his reign.

Beyond the surface narrative of a “shameful” illness, syphilis wielded a profound influence on world history. The disease inadvertently fueled the split within the church and bolstered the rise of Protestantism. The subsequent surge in Puritanism found fertile ground among the populace, driven by warnings of divine retribution for indulging in debauchery.

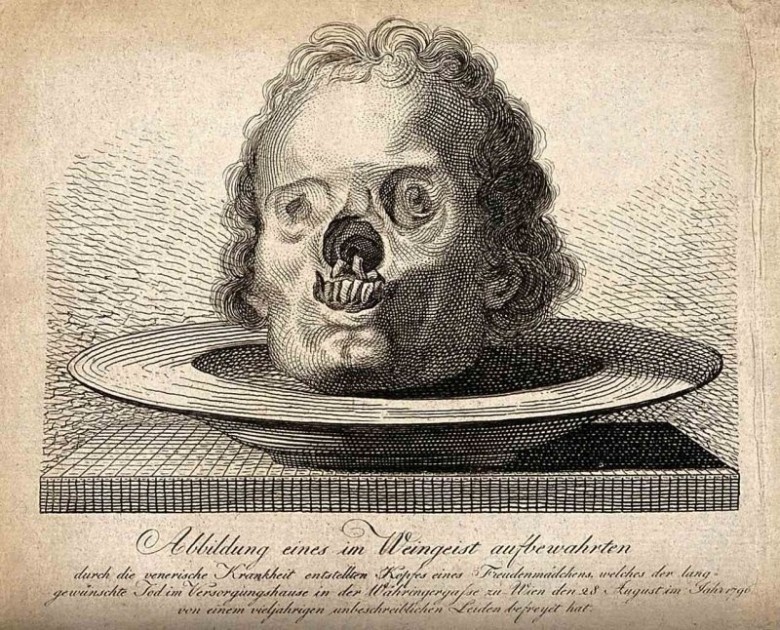

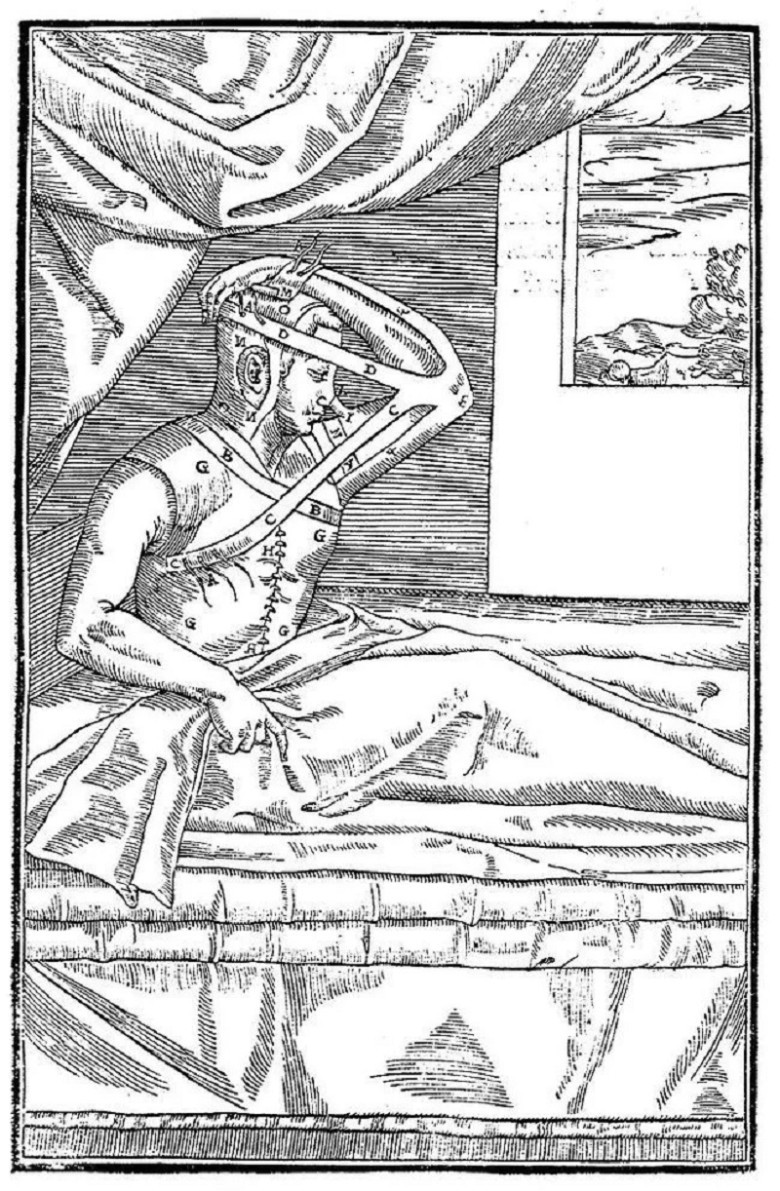

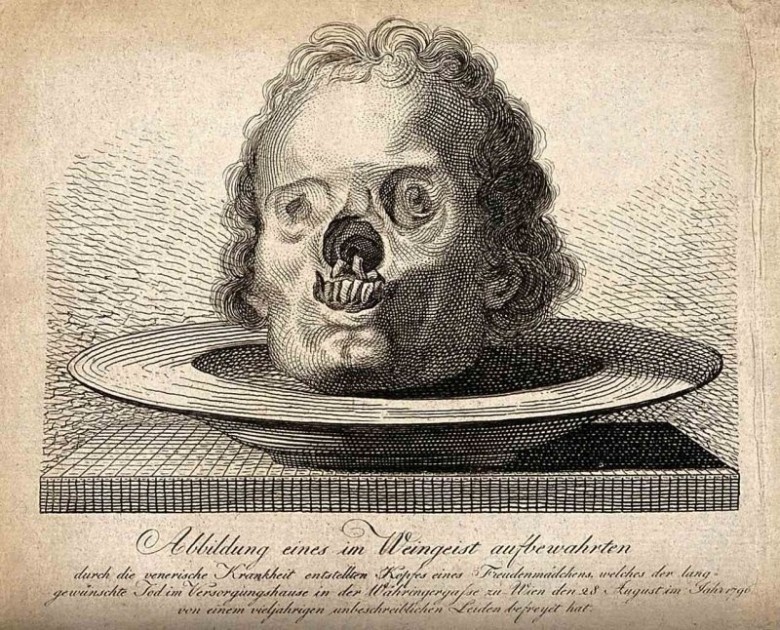

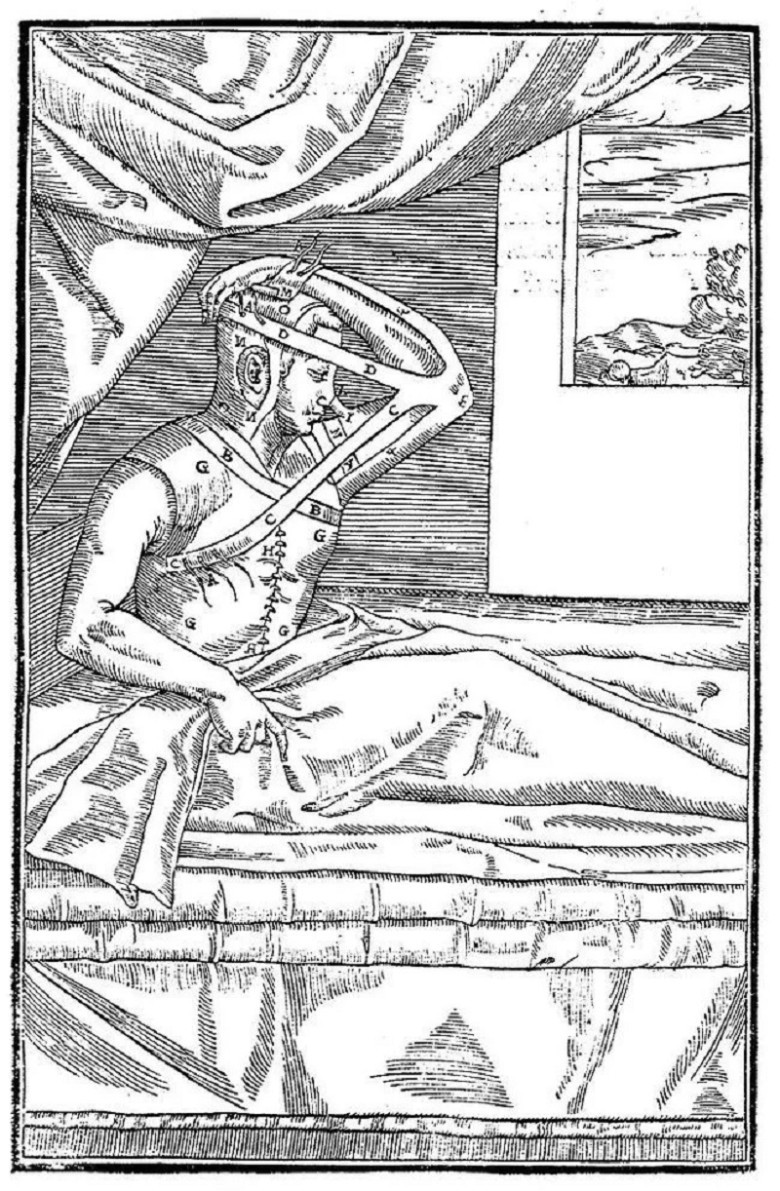

Syphilis also left an indelible mark on cultural practices, such as the popularization of wigs as a means to conceal hair loss resulting from the disease. Additionally, the advent of rhinoplasty can be traced back to the need for reconstructive surgeries to restore collapsed noses afflicted by syphilis. Surgeons devised innovative techniques, including skin grafts from the patient’s arm, to remedy the deformities caused by the disease, showcasing medieval ingenuity amidst adversity.

Furthermore, the impact of syphilis rippled across political landscapes, with the Netherlands leveraging anti-Spanish sentiment by associating Catholics with the spread of the disease. This narrative contributed to the Dutch quest for independence from Spain through propagandist campaigns highlighting the purported role of Catholics in the transmission of syphilis.

Despite staunch warnings from religious figures and common sense measures, syphilis persisted as a prevalent threat, surpassing hunger, wars, and other ailments as a leading cause of mortality. The disease persisted due to the unrestrained sexual behavior prevalent in Europe at the time, undermining efforts to curb its spread.

Notably, the affliction with syphilis extended even to three popes, a testament to the widespread impact and reach of the disease.

Comments

0 comment